Happy Childhood At Stambourne – Part 1

Oh, the old house at home! who does not love it, the place of our childhood, the old roof-tree, the old cottage? There is no other village in all the world half so good as that particular village! True, the gates, and styles, and posts have been altered; but, still, there is an attachment to those old houses, the old tree in the park, and the old ivy-mantled tower. It is not very picturesque, perhaps, but we love to go to see it. We like to see the haunts of our boyhood. There is something pleasant in those old stairs where the clock used to stand; and in the room where grandmother was wont to bend her knee, and where we had family prayer. There is no place like that house after all. — C. H. S.

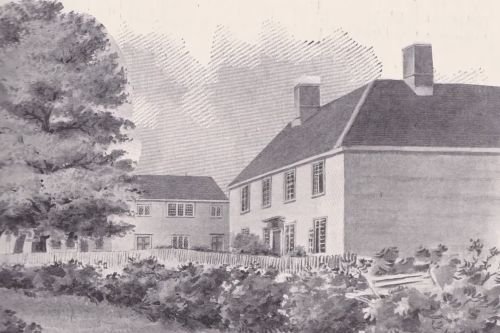

THIS drawing of the old Manse at Stambourne has far more charms for me than for any of my readers; but I hope that their generous kindness to the writer will cause them to be interested in it. Here my venerable grandfather lived for more than fifty years, and reared his rather numerous family. In its earlier days it must have been a very remarkable abode for a dissenting teacher; a clear evidence that either he had an estate of his own, or that those about him had large hearts and pockets. It was in all respects a gentleman’s mansion of the olden times. The house has been supplanted by one which, I doubt not, is most acceptable to the excellent minister who occupies it; but to me it can never be one-half so dear as the revered old home in which I spent some of my earliest years.

It is true the old parsonage had developed devotional tendencies, and seemed inclined to prostrate its venerable form, and therefore it might have fallen down of itself if it had not been removed by the builder; but, somehow, I wish it had kept up forever and ever. I could have cried, “Builders, spare that home. Touch not a single tile, or bit of plaster;” but its hour was come, and so the earthly house was happily dissolved, to be succeeded by a more enduring fabric. The new house, as Smith told me, was “built on the same destruction.” It stood near the chapel, so that the pastor was close to his work.

It looks a very noble parsonage, with its eight windows in front; but at least three, and I think four, of these were plastered up, and painted black, and then marked out in lines to imitate glass. They were not such very bad counterfeits, or the photograph would betray this. Some of us can remember the window tax, which seemed to regard light as a Latin commodity — lux, and therefore a luxury, and as such to be taxed. So much was paid on each aperture for the admission of light; but the minister’s small income forced economy upon him, and so room after room of the manse was left in darkness, to be regarded by my childish mind with reverent awe.

Over other windows were put up boards marked DAIRY, or CHEESE-ROOM, because by being labeled with these names they would escape the tribute. What a queer mind must his have been who first invented taxing the light of the sun! It was, no doubt, meant to be a fair way of estimating the size of a house, and thus getting at the wealth of the inhabitant; but, incidentally, it led occupiers of large houses to shut out the light for which they were too poor to pay.

Let us enter by the front door. We step into a spacious hall, innocent of carpet. There is a great fireplace, and over it a painting of David, and the Philistines, and Giant Goliath. The hall-floor was of brick, and carefully sprinkled with fresh sand. We see this in the country still, but not often in the minister’s house. In the hall stood “the child’s” rocking-horse. It was a gray horse, and could be ridden astride or side-saddle. When I visited Stambourne, in the year 1889, a man claimed to have rocked me upon it. I remembered the horse, but not the man, — so sadly do we forget the better, and remember the baser. This was the only horse that I ever enjoyed riding. Living animals are too eccentric in their movements, and the law of gravitation usually draws me from my seat upon them to a lower level; therefore I am not an inveterate lover of horseback. I can, however, testify of my Stambourne steed, that it was a horse on which even a member of Parliament might have retained his seat.

How I used to delight to stand in the hall, with the door open, and watch the rain run off the top of the door into a wash-tub! How much better to catch the overflow of the rain in a tub than to have a gutter to carry it off! So I thought; but do not now think. What bliss to float cotton-reels in the miniature sea! How fresh and sweet that rain seemed to be! The fragrance of the water which poured down in a thunder-shower comes over me now.

Where the window is open on the right, was the best parlor. Roses generally grew about it, and bloomed in the room if they could find means to insert their buds between the wall and the window-frame. They generally found ample space, for nothing was quite on the square. There had evidently been a cleaning up just before my photograph was taken, for there are no roses creeping up from below. What Vandals people are when they set about clearing up either the outsides or the insides of houses! On the sacred walls of this “best parlor” hung portraits of my grandparents and uncles, and on a piece of furniture stood the fine large basin which grandfather used for what he called “baptisms.” In my heart of hearts, I believe it was originally intended for a punch-bowl; but, in any case, it was a work of art, worthy of the use to which it was dedicated. This is the room which contained the marvel to which I have often referred, —

An Apple In A Bottle

I remember well, in my early days, seeing upon my grandmother’s mantelshelf an apple contained in a phial. This was a great wonder to me, and I tried to investigate it. My question was, “How came the apple to get inside so small a bottle?” The apple was quite as big round as the phial; by what means was it placed within it? Though it was treason to touch the treasures on the mantel-piece, I took down the bottle, and convinced my youthful mind that the apple never passed through its neck; and by means of an attempt to unscrew the bottom, I became equally certain that the apple did not enter from below. I held to the notion that by some occult means the bottle had been made in two pieces, and afterwards united in so careful a manner that no trace of the join remained. I was hardly satisfied with the theory, but as no philosopher was at hand to suggest any other hypothesis, I let the matter rest. One day, the next summer, I chanced to see upon a bough another phial, the first cousin of my old friend, within which was growing a little apple which had been passed through the neck of the bottle while it was extremely small. “Nature well known, no prodigies remain.” The grand secret was out. I did not cry, “Eureka! Eureka!” but I might have done so if I had then been versed in the Greek tongue.

This discovery of my juvenile days shall serve for an illustration at the present moment. Let us get the apples into the bottle while they are little: which, being translated, signifies, let us bring the young ones into the house of God, by means of the Sabbath-school, in the hope that, in after days, they will love the place where His honor dwelleth, and there seek and find eternal life. By our making the Sabbath dreary, many young minds may be prejudiced against religion: we would do the reverse. Sermons should not be so long and dull as to weary the young folk, or mischief will come of them; but with interesting preaching to secure attention, and loving teachers to press home the truth upon the youthful heart, we shall not have to complain of the next generation, that they have “forgotten their resting-places.”

In this best parlor grandfather would usually sit on Sunday mornings, and prepare himself for preaching. I was put into the room with him that I might be quiet, and, as a rule, The Evangelical Magazine was given me. This contained a portrait of a reverend divine, and one picture of a missionstation. Grandfather often requested me to be quiet, and always gave as a reason that I “had the magazine.” I did not at the time perceive the full force of the argument to be derived from that fact; but no doubt my venerable relative knew more about the sedative effect of the magazine than I did. I cannot support his opinion from personal experience. Another means of stilling “the child” was much more effectual. I was warned that perhaps grandpa would not be able to preach if I distracted him, and then, — ah! then, what would happen, if poor people did not learn the way to Heaven? This made me look at the portrait and the missionary-station once more. Little did I dream that some other child would one day see my face in that wonderful Evangelical portrait-gallery.

When I was a very small boy, I was allowed to read the Scriptures at family prayer. Once upon a time, when reading the passage in Revelation which mentions the bottomless pit, I paused, and said, “Grandpa, what can this mean?” The answer was kind, but unsatisfactory, “Pooh, pooh, child, go on.” The child, however, intended to have an explanation, and therefore selected the same chapter morning after morning, and always halted at the same verse to repeat the inquiry, hoping that by repetition he would importune the good old gentleman into a reply. The process was successful, for it is by no means the most edifying thing in the world to hear the history of the Mother of Harlots, and the beast with seven heads, every morning in the week, Sunday included, with no sort of alternation either of Psalm or Gospel; the venerable patriarch of the household therefore capitulated at discretion, with, “Well, dear, what is it that puzzles you?”

Now “the child” had often seen baskets with but very frail bottoms, which in course of wear became bottomless, and allowed the fruit placed therein to drop upon the ground; here, then, was the puzzle, — if the pit aforesaid had no bottom, where would all those people fall to who dropped out at its lower end? — a puzzle which rather startled the propriety of family worship, and had to be laid aside for explanation at some more convenient season. Queries of the like simple but rather unusual stamp would frequently break up into paragraphs of a miscellaneous length the Bible-reading of the assembled family, and had there not been a world of love and license allowed to the inquisitive reader, he would very soon have been deposed from his office. As it was, the Scriptures were not very badly rendered, and were probably quite as interesting as if they had not been interspersed with original and curious inquiries.

I can remember the horror of my mind when my dear grandfather told me what his idea of “the bottomless pit” was. There is a deep pit, and the soul is falling down, — oh, how fast it is falling! There! the last ray of light at the top has disappeared, and it falls on-on-on, and so it goes on falling — on-on-on for a thousand years! “Is it not getting near the bottom yet? Won’t it stop?” No, no, the cry is, “On-on-on.” “I have been falling a million years; am I not near the bottom yet?” No, you are no nearer the bottom yet; it is “the bottomless pit.” It is on-on-on, and so the soul goes on falling perpetually into a deeper depth still, falling forever into “the bottomless pit” — on-on-on — into the pit that has no bottom! Woe, without termination, without hope of its coming to a conclusion!

In my grandfather’s garden there was a fine old hedge of yew, of considerable length, which was clipped and trimmed till it made quite a wall of verdure. Behind it was a wide grass walk, which looked upon the fields; the grass was kept mown, so as to make pleasant walking. Here, ever since the old Puritanic chapel was built, godly divines had walked, and prayed, and meditated. My grandfather was wont to use it as his study. Up and down it he would walk when preparing his sermons, and always on Sabbath-days when it was fair, he had half-an-hour there before preaching. To me, it seemed to be a perfect paradise; and being forbidden to stay there when grandfather was meditating, I viewed it with no small degree of awe.

I love to think of the green and quiet walk at this moment; but I was once shocked and even horrified by hearing a farming man remark concerning this sanctum sanctorum, “It ‘ud grow a many ‘taturs if it wor ploughed up.” What cared he for holy memories? What were meditation and contemplation to him? Is it not the chief end of man to grow potatoes, and eat them? Such, on a larger scale, would be an unconverted man’s estimate of joys so elevated and refined as those of Heaven. Alphonse Karr tells a story of a servant-man who asked his master to be allowed to leave his cottage, and sleep over the stable. What was the matter with his cottage? “Why, sir, the nightingales all around the cottage make such a ‘jug, jug, jug,’ at night that I cannot bear them.” A man with a musical ear would be charmed with the nightingales’ song, but here was a man without a musical soul who found the sweetest notes a nuisance. This is a feeble image of the incapacity of unregenerate man for the enjoyments of the world to come, and as he is incapable of enjoying them, so is he incapable of longing for them.